3. Loops and String Manipulation¶

3.1. while loops¶

Most of the examples of code we’ve seen so far have been fairly short – a few lines here and there. Now we’re going to start looking at programs that are a bit longer. Don’t be too daunted by this. If you practice, you’ll gain comfort with knowing how to break down programs section by section. Let’s go ahead and practice doing this starting with this chapter.

Sometimes we’ll want to repeat an action in code. One example might be that we repeatedly ask the user for input until we run out of that input. Suppose we write a program that calculates the amount of sales tax on different items at a store. We might write the code found in Listing 3.1.

1tax = 0.07 # that is, 7 percent

2print("Enter the amount of each item.")

3print("Enter 'quit' to end the program.")

4amount = input("Amount of item? ")

5while amount != "quit":

6 amount = float(amount)

7 total = (amount * tax) + amount

8 print("The total for that item will be %.2f." % total)

9 amount = input("Amount of item? ")

10print("Thank you for using this program.")

To some readers, this program might look intimidating at first, but each section contains ideas we’ve seen before. We’ve just added one idea after the next. So, what are these familiar code sections? Well, we are getting input from the user. If the input is not the word “quit,” we cast the amount to a float (line 6) and compute the total price of the item with tax included (line 7).

What is special about the above code is the keyword while in line 5. while

works similar to if in many ways. When we use if, we specify a Boolean

condition immediately after the word if, and if the condition is True,

Python executes the code that is indented beneath it. while works the same

way, however, once we reach the end of the indented block, the code “loops” back

up to the condition again. If the condition is again True, we reenter the

indented block of code. Thus, we can make code repeat itself as long as a

condition is met. A programming language “construct” that allows code to be

repeated is known as a loop.

We call the expression amount != "quit" in Listing 3.1

the loop condition.

We call the indented block of statements that follows the loop condition the

loop body. We say that the statements in the indented block are inside the

loop body. The final print statement in line 10 of

Listing 3.1 is not indented and is therefore outside the loop

body.

Try out the code above if you haven’t already. Does it behave the way you expect?

Now, notice that we ask for input twice in this program: once just before we try

to enter the loop (line 4), and once at the end of the indented block inside the

loop body (line 9). Why? The value returned by the initial input statement

gets us into the loop body, though it doesn’t have to. It is possible that the

user types “quit” right away, in which case the program bypasses the loop and

prints our “thank you” message. At the end of the loop body, we need to ask the

user for the next input value, so that we have a new amount. Otherwise, the

program would just continue to calculate the same total value over and over

again and the program would never have the chance to end.

To see this for yourself, delete the last line of the loop body in

Listing 3.1, i.e., delete line 9. Instead of deleting it, you

could just comment it out by putting a # symbol at the start of that line.

Run your code and type an initial amount, say, 4.00. Your code will endlessly

compute sales tax with no end in sight! Press the “Control” and “C” keys

simultaneously to abort your program (we will write this Ctrl+C in the future

because that’s how programmers write such things).

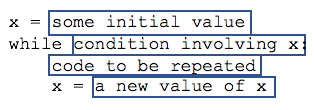

With this in mind, we will often see loops written using the pattern in Figure 3.1.

Fig. 3.1 A common while loop¶

We call each new time through the body of the loop an iteration. We may refer to the first iteration, second iteration, next iteration, final iteration, etc., when discussing the behavior of a loop.

To get a sense of the mechanics of how while loops work, beginning programmers

often consider “toy” examples that showcase a number of “gotchas” when it comes

to programming loops. Consider Listing 3.2.

1x = 1

2while x <= 5:

3 print(x)

4 x = x + 1

5print("Done.")

Run it. This prints the following.

1

2

3

4

5

Done.

We don’t always need to have a non-indented statement following a loop. We are only doing this in the examples so it is clear in the output that we left the loop body.

In each iteration, we print the value of x and then increase x by 1.

Adding 1 to a value is such a common thing in programming that it has a

special name: increment. That is, we are incrementing x by adding

1 to it. When x eventually becomes 5, we print the 5 and

then add 1 more to make x` become 6. When we evaluate the

expression x <= 5, we get 6 <= 5, which is False, so our code

falls down to the non-indented section of code.

It is good to observe that, in this example, the last value we print is 5, but

the value of x when we exit the loop is 6.

Let’s look at another “toy” example. We will modify Listing 3.2, which was the following.

1x = 1

2while x <= 5:

3 print(x)

4 x = x + 1

5print("Done.")

Notice that we’ve highlighted the statements that form the loop body. Let’s change the order of those loop body statements to see what, if any, effect it has (Listing 3.3).

1x = 1

2while x <= 5:

3 x = x + 1

4 print(x)

5print("Done.")

Run it. Our output is different from the first example.

2

3

4

5

6

Done.

Can you explain why this is?

In Listing 3.3, we are incrementing x before we print it.

Thus, the first value we print is not 1 but 2. The order of statements

matters in programming, and it definitely matters in loops!

Consider another example (Listing 3.4).

1x = 1

2while x <= 5:

3 print(x)

4print("Done.")

Here, we have removed the line that increments x. You should be able to guess

what will happen when we run this program (hint: be ready to press Ctrl+C).

Since we have removed the line that increments x, x never changes, and so

the program just prints 1 over and over again. Loops that are never-ending

are called infinite loops. You will inadvertently create infinite loops every

now and then when you program. It becomes very important to know how to debug

them.

Let’s try another example (Listing 3.5).

1x = 0

2while x <= 4:

3 print(x)

4 x = x + 1

5print("Done.")

All we’ve done is changed the initial value of x and the value of x that

causes us to not reenter the loop. The output is:

0

1

2

3

4

Done.

Let’s make a small change to Listing 3.5. Suppose we change line 2 so that the code appears as it does in Listing 3.6.

1x = 0

2while x < 4:

3 print(x)

4 x = x + 1

5print("Done.")

Now instead of <=, we have <. This makes the code end the loop one value of

x earlier. The output is:

0

1

2

3

Done.

Let’s change the condition in line 2 again so that it uses > instead of <.

The code now reads as in Listing 3.7.

1x = 0

2while x > 4:

3 print(x)

4 x = x + 1

5print("Done.")

What is the output? Why?

The output is (as you may or may not have expected):

Done.

The variable x is set to zero initially. In the next line, the expression x >

4 becomes 0 > 4, which is False. Thus, the code bypasses the loop body

entirely. There is no “rule” that says we have to do the loop body at least

once. Computers are stupid. They only do what you tell them to. In this case,

because the condition is False initially, we never do the loop body and go

straight to the non-indented line of code past the loop body.

All of our “toy” examples thus far have involved incrementing a loop variable x, that is, adding 1 to x. However, we can change our variable however we wish. We could create the code in Listing 3.8.

1x = 2

2while x <= 8:

3 print(x)

4 x = x + 2

5print("Who do we appreciate?")

In this code, we add 2 to x each time. The output of this code is:

2

4

6

8

Who do we appreciate?

We’ve used the heck out of the variable name x. Let’s pick a different name

for a while just for the sake of using something different. In

Listing 3.9, we will use the name count for our loop variable

name.

1count = 5

2while count > 0:

3 print(count)

4 count = count - 1

5print("Blastoff!")

In this code, we subtract 1 from count each time. This is called

decrementing count. The output of this code is:

5

4

3

2

1

Blastoff!

Toy examples are a great way to understand how loops work from a “mechanical” perspective, but let’s see how we can use them to solve real problems. Recall our very first example in this section, Listing 3.1, which dealt with reporting the price of an item after sales tax. Our next example is also related to money. Suppose we open a savings account, one that pays 5% interest per year into the account as long as we don’t withdraw any money that we deposit. Let’s say we start the account by depositing $10,000.00. How many years will it take to double our investment?

Mathematicians would attempt to derive an equation to solve this problem, but with computers we don’t have to. We can make the computer figure it out for us. We just need to know how to write the code to tell the computer what to do.

The question “How many years will it take to double our investment?” tells us a

lot about the code we would need to write. We would need to keep track of our

balance as it grows by 5% each year. We would need to keep track of the number

of years that have elapsed so far in our code. We would also need to check to

see if the balance has doubled. If, in describing what our program is supposed

to do, we say we need to check something, we are often talking about a Boolean

condition found in an if statement or a while loop.

Try to program this example on your own first. You can’t learn to be a good programmer if you don’t try things regularly by starting with a blank screen or a blank sheet of paper. If you get really stuck, then (and only then) glance at the answer below.

Okay, let’s look at a solution found in Listing 3.10 (Warning: Our initial solution will have flaws, as initial solutions often do).

1balance = float(input("Enter starting balance: "))

2years = 0

3while balance < 2*balance:

4 balance = balance * 0.05 + balance

5 years = years + 1

6 print("The balance after %d years is $%.2f." %

7 (years, balance))

8print("It will take %d years to double your investment." % years)

This is a good first attempt. Here, we are letting the loop do the work of

adding to the balance year after year, each time checking to see if the balance

has doubled and if we can leave the loop. However, our logic is flawed a bit.

Consider the loop condition balance < 2*balance. A variable’s value will never

be greater than twice itself (unless that value is negative, but let’s steer

clear of negative values in bank accounts!).

The problem here is that we’re trying to use the variable balance for two very

different purposes simultaneously. On one hand, we are using balance to keep

track of the current balance as it changes year after year. On the other hand,

we’re pretending that it still holds the starting balance from our initial

investment. We should really keep the starting balance in a separate variable,

which we will name startbalance.

With this in mind, we can modify the previous code as follows in Listing 3.11.

1startbalance = float(input("Enter starting balance: "))

2balance = startbalance

3years = 0

4while balance < 2*startbalance:

5 balance = balance * 0.05 + balance

6 years = years + 1

7 print("The balance after %d years is $%.2f." %

8 (years, balance))

9print("It will take %d years to double your investment." % years)

3.2. Manipulating and printing strings¶

Given our newly found exposure to loops, now is a good time to revisit strings.

It turns out, there is a fair amount of nifty stuff we can do with strings using

loops. Suppose we create a new string variable named s in the following way.

s = "abc def"

Programmers sometimes talk about different important parts of a string. They

call these parts substrings. There are a lot of different possible substrings

of "abc def" including "a", "ab", and "def", just to name a few. The

string "" is also technically a substring of s. Note that "" is different

from " ". The former is called the empty string; it is a string without any

characters. The latter is a string with a single space in it.

Note that the string s contains a space between the substrings "abc" and

"def". That will become an important observation later. Now, we can inspect

individual characters by using square brackets and character’s position in the

string. Consider the following example.

print(s[0])

print(s[1])

print(s[2])

print(s[3])

print(s[4])

print(s[5])

print(s[6])

print(s[7])

If we run this code, we see the following output.

a

b

c

d

e

f

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/Users/shep/cs1/code/ch3strings.py", line 9, in <module>

print(s[7])

IndexError: string index out of range

The syntax for retrieving a single character from a string s is s[index]

where index is an integer representing the position of the character we wish

to retrieve. The first character (in this case "a") is at position 0 rather

than position 1. That may take a little getting used to. We will use the

words “index” and “position” interchangeably to describe the location of a

character in a string (also, note that the plural of “index” is “indices”).

Let’s re-list the code again, this time with comments to explain each line

(see Listing 3.12).

1s = "abc def"

2print(s[0]) # print "a"

3print(s[1]) # print "b"

4print(s[2]) # print "c"

5print(s[3]) # print " " (which ends up as just a blank line)

6print(s[4]) # print "d"

7print(s[5]) # print "e"

8print(s[6]) # print "f"

9print(s[7]) # Kablooey! There is no character at index 7.

Between the square brackets, you can place one index or you can give a range of indices, as we see in Listing 3.13.

1s = "abc def"

2print(s[0:2])

3print(s[0:3])

4print(s[3:6])

5print(s[3:])

6print(s[:4])

This code yields the following output.

ab

abc

de

def

abc

We can observe that the first print in line 2 of Listing 3.13

does not print characters at indices 0 through 2. Rather, it prints

characters at positions 0 and 1 but not 2. We might conclude from this

that when we have two indices in square brackets following a string, the first

number is the first position inclusive and the second number is the last

position that will be selected up to, but not including, or exclusive. Note

that the indices are separated by a colon (:). In this situation, we will call

the colon the slicing operator.

Lines 4 and 5 in Listing 3.13 show us that the first and second indices of the slicing operator are optional. If one is omitted, Python assumes that the we mean “go to the ends of the string.” When we use square brackets to select one or more characters from a string, we say that we are obtaining a substring of the original string. Obtaining a substring from some original string in this manner is called string slicing.

What appears to be indentation in lines 3 and 4 of the output is actually the

single space found at index 3 in the string s. It is difficult to tell if there

is a space at the end of line 5. One way to tell is to append an additional

character to the output to see the space. For example:

print(s[:4] + "$")

The output is:

abc $

Can you see the space in the output above?

There are quite a few things we can do with strings. Another interesting feature of strings is that they have their own set of special functions. Consider Listing 3.14.

1t = "I like cheese."

2shout = t.upper()

3print(shout)

Most of the functions we have seen thus far (like print, input, etc.) do not

have a period/dot in front of them. Calling a function which operates

specifically on a value or a variable uses dot-notation, like t.upper().

On the Internet, typing something in all capital letters is a convention that indicates shouting. In effect, the upper() function can be used on a string value (which is often contained in a variable) to return an all-uppercase version of that string. The output of Listing 3.14 is:

I LIKE CHEESE.

It is very important to note that upper() does not change the contents of the

string variable t. If I do this:

t = "I like cheese."

shout = t.upper()

print(shout)

print(t)

I get this as output:

I LIKE CHEESE.

I like cheese.

Notice that the contents of t are still "I like cheese.".

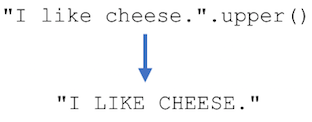

Functions like upper() are not restricted to being called on variables. They

may be called on any string value, like this:

shout = "I like cheese.".upper()

print(shout)

This works because Python transforms the first statement as shown in Figure 3.2.

Fig. 3.2 String transformation¶

A common mistake is to omit the parentheses at the end of upper(). Remember

that upper is just the name of the function; the parentheses are what calls

the function. If we remove the parentheses, we get output that looks strange (Listing 3.15).

1t = "I like cheese."

2print(t.upper)

This produces something like:

<built-in method upper of str object at 0x1019807e8>

This is Python’s way of saying “yes, upper is the name of a function. If you

want to actually use that function, put parentheses at the end.” Let’s add the

parentheses to the end of the function call

(Listing 3.16).

And now, it works.

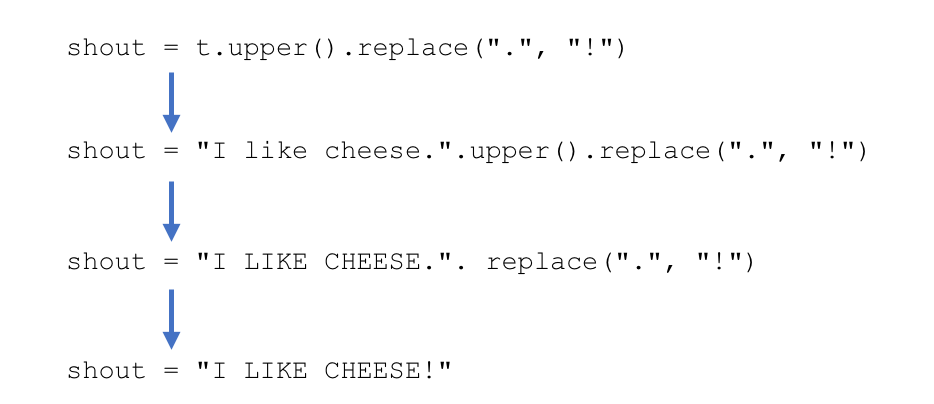

Observe that when we “shout” by using upper(), the punctuation displayed is a

period. Shouldn’t we change that to an exclamation point? Consider the

following code in Listing 3.17.

1t = "I like cheese."

2shout = t.upper().replace(".", "!")

3print(shout)

The function replace is another string function. It takes two arguments. The

first is a pattern to find in the string, and the second is a string we wish to

insert instead.

Consider how Python executes line 2 of Listing 3.17 (see Figure 3.3).

Fig. 3.3 String replace transformation¶

This example works because t is a string, so calling t.upper() returns

another string. And, because t.upper() is a string, we can call replace on

it to return yet another string. Calling a series of functions in one line is

called function chaining.

Note that the original string value of t still hasn’t changed. t is still

"I like cheese.". If we wanted to actually change t, we would need to use

an assignment statement as in Listing 3.18.

t = t.upper().replace(".", "!")

Now, t is changed to the newly returned string value.

We can even chain calls to replace (see Listing 3.19):

t = t.upper().replace("LIKE","LOVE").replace(".", "!")

As you might guess, and in the interest of completeness of our discussion, in

addition to upper there is a function named lower for returning all

lowercase versions of strings.

Now, let us explore the relationship between strings and loops. Consider the code in Listing 3.20.

1s = "abc def"

2index = 0

3while index < 7:

4 print(s[index])

5 index = index + 1

Listing 3.20 produces the following output:

a

b

c

d

e

f

Why?

The variable index starts at 0. Each time in the loop body, we print the

value of the expression s[index], which in the first loop iteration is s[0],

which has the value "a". The code adds 1 to index, so now index is 1

(it was 0 previously). The code loops back around to the beginning of the

loop. We print the value of s[index] again, which this time is s[1], and

s[1] is "b". We continue in this fashion with each iteration of the loop

having a new value of index. Eventually, index becomes 7, at which point

we exit the loop.

This is yet another “toy” example intended to get us to see the relationship between loops and strings, which is a powerful relationship we will exploit very shortly.

Let’s make one change to Listing 3.20. We will change only

the value of the string variable s. Our new code is in

Listing 3.21.

1s = "protagonist"

2index = 0

3while index < 7:

4 print(s[index])

5 index = index + 1

The output is now:

p

r

o

t

a

g

o

Oh no! Where is the rest of the string? Why did it stop after 7 characters?

Unfortunately, we have hard-coded the loop condition as index < 7. We could

change the value of s, and we shouldn’t assume the length of s will always

be 7 characters. From a logic standpoint, the 7 is supposed to refer to the

length of the string, which is also 1 more than the last index in the string.

Recall from the previous example that the last index of s was 6 and the

number of characters (the length of the string) was 7. In

Listing 3.21, the length of the string is 11,

not 7.

Any time we hard-code a value, like 7, it makes our code brittle and less

resistant to change. Let us replace this line:

while index < 7:

with this line:

while index < len(s):

The len function returns the number of characters in the string. Our new code

is shown in Listing 3.22.

1s = "protagonist"

2index = 0

3while index < len(s):

4 print(s[index])

5 index = index + 1

Alternatively, we could have done things a little differently. See Listing 3.23 and note the highlighted lines.

1s = "protagonist"

2index = 0

3lastindex = len(s) - 1

4while index <= lastindex:

5 print(s[index])

6 index = index + 1

We have created a new variable named lastindex. In the case of the string

"protagonist", the value of lastindex will be 10 since len(s) is 11.

It is very important to see the relationship between the last index and the

length of the string. Because indices start at 0, not 1, the last index is

always the length minus 1 (in this case, the value of the expression

len(s)-1).

Let’s see how well this is all sinking in. Can you write code to print the

characters of a string, one on each line, but in reverse order this time? In

other words, if my string is "abc", can you write code that prints:

c

b

a

Give it a try.

Let’s check your work. With some experimentation, you might have been able to get close to a solution that looks like the code in Listing 3.24. (If not, keep trying and practicing.)

1s = "abc"

2index = len(s) - 1

3while index >= 0:

4 print(s[index])

5 index = index - 1

Note that we are setting the initial index variable to the last index of string

(again, length minus 1), and in our loop body we are subtracting 1 rather

than adding 1.

In Python, as it is in other programming languages, there is often more than one way to write a program. Another approach to printing a string in reverse could take advantage of the fact that you can put negative indices in square brackets to obtain characters in a string starting from the end rather than from the beginning. For example, suppose we have the following code.

foo = "abc"

print(foo[-1])

print(foo[-2])

print(foo[-3])

This prints:

c

b

a

With this in mind, we could write new code that produces the same output as Listing 3.24, but in a different way. Consider Listing 3.25.

1foo = "abc"

2index = -1

3while index >= -len(foo):

4 print(foo[index])

5 index = index - 1

Note the loop condition. If len(foo) in this case is 3, then -len(foo) is

-3.

(Why did we name our variable foo? That’s weird, right? You’re correct; it

is weird! There’s a historical reason why computer science books often name

variables foo and bar. Search the Web for foobar and its original form

FUBAR so that you can learn where this nomenclature comes from.)

3.3. for loops¶

Loops of the form found in Listing 3.26 are very common.

Suppose n is an integer variable defined earlier in a program.

k = 0

while k < n:

print(k)

k = k + 1

Loops of this form are so common, in fact, that there is a shorter version of

the loop known as a for loop. Listing 3.26 could be

re-written as a for loop as shown in Listing 3.27.

for k in range(0, n):

print(k)

Gone is the explicit declaration of the variable k. Gone also is the

increment statement k = k + 1. The range expression gives k an initial

value of 0 in this example, and then it allows the loop to continue until k ==

n, at which point the computer leaves the loop.

Recall Listing 3.22 in Section 3.2,

which is shown below. To print the characters of a string, each on a separate line,

using a while loop, we could write:

1s = "protagonist"

2index = 0

3while index < len(s):

4 print(s[index])

5 index = index + 1

We can now re-write this code using the shorter, more succinct for loop (see Listing 3.28).

1s = "protagonist"

2for index in range(0, len(s)):

3 print(s[index])

for loops can also countdown or count in multiples just as easy as while

loops can. Suppose we want to print a string in reverse order like we did in

Listing 3.24. As a reminder, the code looked like this:

1s = "abc"

2index = len(s) - 1

3while index >= 0:

4 print(s[index])

5 index = index - 1

Instead, we can add a third argument to range which specifies what we add to

the loop variable to change it prior to each iteration of the loop. Thus, we

can do this (Listing 3.29).

1s = "cba"

2for index in range(len(s)-1, -1, -1):

3 print(s[index])

That’s a lot to mentally unpack. Let’s take it a piece at a time. Let’s take the first emphasized expression in the range function below.

for index in range(len(s)-1, -1, -1):

This sets the last index in the string len(s)-1 as the initial value of the

variable index. The next expression/value we wish to emphasize in range is:

for index in range(len(s)-1, -1, -1):

This says that when index goes past 0 and reaches -1, we should exit the

loop. Finally, we have:

for index in range(len(s)-1, -1, -1):

This -1 specifies how index should be changed prior to each iteration. This

means that index will have 1 subtracted from its value.

Let’s see how we are doing here. Suppose I have the code in Listing 3.30.

1for i in range(1, 9, 2):

2 print(i)

What is the output of this code?

We would expect to see the following on-screen.

1

3

5

7

Can you explain why?

The variable i gets the value 1 to start the loop. In each iteration, the

value of i is printed. Just before each iteration, we add 2 to i.

Therefore, i will have the values 1, 3, 5, and 7 within the loop body.

When i reaches 9, the for loop will end.

Let us try to use our knowledge of for loops to write a program that reverses

a string. In other words, given user input, reverse the input and print it to

the user. If the user enters "abc def", then the program should output "fed

cba".

Here is our attempt (Listing 3.31 ).

1s = input("Enter a string: ")

2rev = ""

3for i in range(len(s)-1, -1, -1):

4 rev = rev + s[i]

5print("The reverse of the string is: %s." % rev)

s is the input string variable and rev will be the string variable that

holds s’s reverse. We take each character from s using a for loop and we

concatenate it onto the end of rev.

Consider how rev changes with each iteration of the loop, as shown in

Table 3.1.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.1 is known a trace table. It serves as a tool for programmers to make sense of how values change from iteration to iteration of a loop.

3.4. for loops with strings, revisited¶

We’ve barely scratched the surface of what for loops can do for us. for

loops in Python have a nifty additional form that allows us to write even

simpler, more readable code. We’ll explore this alternate form now. Let’s set it up in the context of an example. Suppose we wish to iterate through the characters of a string s with the intent of reversing it. We might write the code found in Listing 3.32.

1s = input("Enter a string: ")

2rev = ""

3for index in range(0, len(s)):

4 rev = s[index] + rev

5print("The reverse of the string is: %s." % rev)

Notice how we’ve changed the logic from what we did in

Listing 3.31, our previous attempt. In the previous code, we

traversed the string starting at its last character and working towards its

first character, and for each character, we appended it to the end of the

reversed string rev. In this code (Listing 3.32), we are

doing the opposite. We are traversing the string from first character (the

“front” of the string) to last character (the “back” of the string) and

prepending the character to the front of the reversed string rev. Both

methods solve the same problem and produce the same output.

As it turns out, we don’t even need to concern ourselves with having an index

variable. Python has a version of the for loop syntax that operates

exclusively on strings. Consider the following highlighted adjustments to

Listing 3.32 shown in Listing 3.33.

1s = input("Enter a string: ")

2rev = ""

3for ch in s:

4 rev = ch + rev

5print("The reverse of the string is: %s." % rev)

In this form of the Python for loop, the loop variable ch is assigned a

different character from the string s each time the loop condition is checked.

Notice that there is no more index variable or range function.

3.5. Loops for input validation and translation¶

We have been asking users for input in many of our previous examples. We have always assumed users will type the correct information, but what happens when they do not. Suppose we ask users to enter their age. We have been doing this as follows.

age = int(input("Enter your age: "))

What if users’ fingers slip and they enter "1r" instead of "14"? The int

function will crash because "1r" cannot be cast to an integer. This happens

because we have prematurely tried to cast the string to an integer without

checking the input first. We need to wait to perform the int cast until we

know it is safe to do so. Another way to say this is we need to postpone the

type conversion until we have validated the input. The code in

Listing 3.34 demonstrates how we might do input validation before

casting a string to an integer.

1age_str = input("Enter your age: ")

2while not age_str.isdigit():

3 print("That is not a valid age.")

4 age_str = input("Enter your age: ")

5age = int(age_str)

isdigit (line 2 of Listing 3.34) is a function that we can

always use on a string value. The “dot” (.) separates the word isdigit from

the string it refers to, in this case the value stored in the variable

age_str. age_str.isdigit() returns True if every one of the characters in

age_str are numbers, otherwise it returns False.

(Note: What do you suppose would be the value of the expression "".isdigit()?

In other words, is the result of isdigit going to be True or False

when the string contains no characters at all. You may wish to try typing

this statement into the Python Shell for yourself to see what happens.)

Let us examine another example that uses loops to operate on strings. Suppose we ask users for their full names using an input statement.

fullname = input("Enter your full name: ")

The variable fullname could contain "Javier Sanchez", "Mary Johnson", or

just about anything, though in most cases, there will be a first name and a last

name separated by a space. Let us try to extract the first name from the value

in fullname. To do this, we’ll need to use the slicing operator (:).

Depending on the length of the first name, the range of the string slice will be

a little different.

# Suppose fullname == "Javier Sanchez"

# 01234567...

firstname = fullname[0:6]

# Or, suppose fullname == "Mary Johnson"

# 01234567...

firstname = fullname[0:4]

Since we can’t possibly know the length of the first name ahead of time, we will

need to find the index of the space in order to slice the appropriate substring.

If we are able to put the index of the space into a variable named space, then

we can extract the first name as follows.

firstname = fullname[0:space]

If fullname is "Javier Sanchez" then space would be 6, if fullname is

"Mary Johnson" then space would be 4, and so on. Finding the index of the

space requires us to search the string character by character, which is

something we have already done, both with while loops and with for loops.

Here is our strategy. We will use a loop to examine each character in

fullname, one at a time. If we encounter the space, we will set the value of

space to the current index of the loop, and then we will jump out of the loop

using the command break. After all, once we’ve found the space, our work is

done; there is no need to keep looping.

Thus, our code appears in Listing 3.35.

1fullname = input("Enter your full name: ")

2for index in range(0, len(fullname)):

3 if fullname[index] == ' ':

4 space = index

5 break

6

7firstname = fullname[0:space]

8print("Your first name is %s." % firstname)

Try out this code on several full names that you can think of. Try to find edge cases that may not work. Edge cases are exceptional cases of program input that could cause your code to fail. One such edge case in this problem is full names that do not have spaces, i.e., the names of individuals who only have one name. Consider celebrities’ names such as Prince, Cher, Sting, Madonna, etc. Those names are their full names and first names simultaneously. Try typing “Prince” in as the input to your program.

Enter your full name: Prince

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/Users/shep/cs1/code/ch3fullname.py", line 6, in <module>

firstname = fullname[0:space]

NameError: name 'space' is not defined

Can you explain this error to yourself? Why is space not defined in line 6?

Where in the code do we create the space variable normally?

In this case, space is first created inside the loop (see line 4).

This is generally bad

programming practice. If the variable is used by code outside of a loop, the

variable should also be defined outside the loop. So, let’s define space

before we reach the loop, but what should be its initial value? Let’s choose a

value that doesn’t look like a normal index. Normal indices would be 0, 1,

2, 3, etc., so let’s choose -1 as the initial value of space.

Our code can now be written as in Listing 3.36. Notice

line 3.

1fullname = input("Enter your full name: ")

2

3space = -1

4for index in range(0, len(fullname)):

5 if fullname[index] == ' ':

6 space = index

7 break

8

9if space == -1:

10 firstname = fullname

11else:

12 firstname = fullname[0:space]

13

14print("Your first name is %s." % firstname)

Finding a character or a pattern in a string is such a common operation, Python

gives us a way to do it without writing a loop every time. We can simplify the

code above using the find function as follows in Listing 3.37.

1fullname = input("Enter your full name: ")

2

3space = fullname.find(" ")

4

5if space == -1:

6 firstname = fullname

7else:

8 firstname = fullname[0:space]

9

10print("Your first name is %s." % firstname)

find (line 3 of Listing 3.37) is a function that we can

always use on a string value. The “dot” (.) separates the word find from

the string it refers to, in this case the value stored in the variable

fullname. The argument is the single character or multiple character pattern

to search for. find returns the index where that pattern starts in the value

of fullname.

Here are some examples of using find.

print("abcde".find("b")) # prints 1

print("abcde".find("cd")) # prints 2

print("abcde".find("cash")) # prints -1, which indicates the

# pattern was not found

print("abcde".find("abcde")) # prints 0

Now that we know how to find a pattern (and specifically, a space) in a string, consider what that allows us to do. Suppose we have a sentence that we wish to break into individual words. How are words separated in the English language? If you said “using spaces” then you are correct (for the most part).

Let’s try to do something like this through an example. If you spend time on the Web, you might have learned that Internet citizens have tabbed September 19th as “International Talk Like a Pirate Day.” Imagined pirate-speak draws from many sources in popular culture. Fictional pirates might say “Ahoy!” instead of “Hello!” or they might use the word “matey” to describe a friend. If we wanted to translate a single English word into its Pirate equivalent, we might do something like Listing 3.38.

1english_word = input("Enter a word: ")

2if english_word == "hello":

3 pirate_word = "ahoy"

4elif english_word == "friend":

5 pirate_word = "matey"

6else:

7 # The word has no known pirate translation.

8 # Leave it in English.

9 pirate_word = english_word

10print("%s in pirate is %s." % (english_word, pirate_word))

What if we wanted to change an entire English sentence into Pirate instead of just translating a single word? How would we accomplish that?

Let’s keep this as simple as possible, so for now let’s ignore “edge cases” like uppercase letters and punctuation. Let’s only worry about translating all-lowercase words separated by spaces.

You might not have any idea how to accomplish this in code, but there are a number of ways to get started. One way is to realize that every computer program tends to take input and transform it into output. If we envision a program as taking variables and changing their values in order to reach a goal, we can write down how we want those variables to change, and then write down the code to perform the changes.

Let’s think about what variables we would want to have to make an

English-to-Pirate translator program work. Suppose we have two variables, one

named sentence and the other named word. sentence contains the English

sentence the user types, and word will store each word as we extract it from

sentence. Each time we extract an English word into word, the string in

sentence should shrink.

Again, if we are thinking about a program as something that makes changes to

input variables, we can envision a program looping to change sentence and

word repeatedly. Here is an example.

word: "" sentence: "hi there my friend"

word: "hi" sentence: "there my friend"

word: "there" sentence: "my friend"

word: "my" sentence: "friend"

word: "friend" sentence: ""

Think of this process in a loop. Each time through the loop, we find the index

of the space in sentence and put that index into a variable named space. We

use the slicing operator to get the first word in the sentence from 0 to

space. Then, we use the slicing operator again to “shrink” sentence so that

sentence only contains the remaining words.

This would allow us to translate each word, one at a time. Let’s write some code. Our first attempt is found in Listing~ref{code:pirate_sent1}.

1sentence = input("Enter an English sentence: ")

2word = ""

3print("word: \"%s\", sentence: \"%s\"" % (word, sentence))

4

5space = sentence.find(" ")

6while space != -1:

7 word = sentence[0:space]

8 sentence = sentence[space+1:]

9 print("word: \"%s\", sentence: \"%s\"" % (word, sentence))

10 space = sentence.find(" ")

Let’s try it out.

Enter an English sentence: hello there my friend

word: "" sentence: "hello there my friend"

word: "hello" sentence: "there my friend"

word: "there" sentence: "my friend"

word: "my" sentence: "friend"

This is pretty good, but what about the final word in this example: “friend”. Since there is no space trailing the last word in the sentence, we will need to add some code after the loop to take care of the last word. Consider Listing 3.40.

1sentence = input("Enter an English sentence: ")

2word = ""

3print("word: \"%s\", sentence: \"%s\"" % (word, sentence))

4

5space = sentence.find(" ")

6while space != -1:

7 word = sentence[0:space]

8 sentence = sentence[space+1:]

9 print("word: \"%s\", sentence: \"%s\"" % (word, sentence))

10 space = sentence.find(" ")

11

12if sentence != "":

13 word = sentence

14 sentence = ""

15 print("word: \"%s\", sentence: \"%s\"" % (word, sentence))

The highlighted block of code in Listing 3.40 checks to see

if there’s still text residing in sentence.

Now all that’s left is to do the translating. We will take each word and

append its translation to a new string which we’ll call pirate. We can get

rid of our print statements, too, since they were only there to aid our

understanding of what the code does. Listing 3.41 is our

final code.

1sentence = input("Enter an English sentence: ")

2word = ""

3pirate = ""

4

5space = sentence.find(" ")

6while space != -1:

7 word = sentence[0:space]

8 sentence = sentence[space+1:]

9 if word == "hello":

10 pirate = pirate + "ahoy" + " "

11 elif word == "friend":

12 pirate = pirate + "matey" + " "

13 else:

14 pirate = pirate + word + " "

15 space = sentence.find(" ")

16

17if sentence != "":

18 word = sentence

19 sentence = ""

20 if word == "hello":

21 pirate = pirate + "ahoy" + " "

22 elif word == "friend":

23 pirate = pirate + "matey" + " "

24 else:

25 pirate = pirate + word + " "

26

27print("Your sentence translated to pirate is:")

28print(pirate)

An example of a running program is:

Enter an English sentence: hello there my friend

Your sentence translated to pirate is:

ahoy there my matey

We can add more translations by adding more elif conditions to the if-blocks

of statements, though we must add them both to the while loop code and the

if-block that follows the while loop. Having to add this logic in two

different places makes the code more difficult to maintain, since we might add

an elif to the earlier part of the code but then forget to add it to the later

part of the code. In Chapter 4, we will examine functions,

which will improve the maintainability of this code dramatically.

3.6. Nested loops¶

Some interesting and practical things happen when we use a loop as the body of another loop. Consider Listing 3.42, and try to guess its output (Well, don’t guess! Actually try to reason your way through the code. Guessing is for lazy fools!).

1for outer in range(0, 3):

2 for inner in range(0, 3):

3 print("outer = %d, inner = %d" % (outer, inner))

Let’s follow the code step-by-step as we would with any code. The first

statement we encounter is for outer in range(0, 3). Since this is first time

we’ve encountered this statement, this code sets outer to 0 and we enter its

loop body. The first statement of the loop body is, of course, another loop.

This loop statement is for inner in range(0, 3). So, this sets inner to 0

and we enter its loop body. This means that at this point in the code, we are

actually inside two loops: an inner one, which is inside an outer one. The

first (and only) statement in the inner loop prints the values of outer and

inner so that we can see how the values change throughout the program.

We call a loop-inside-a-loop construct a set of nested loops. That is, the inner loop is nested inside the outer loop.

Before we continue discussing how these loops work, run the code to see the output.

outer = 0, inner = 0

outer = 0, inner = 1

outer = 0, inner = 2

outer = 1, inner = 0

outer = 1, inner = 1

outer = 1, inner = 2

outer = 2, inner = 0

outer = 2, inner = 1

outer = 2, inner = 2

We can get a pretty good idea of how this works from looking at the output.

Once we enter the outer loop, we encounter the inner loop right away. Python

will stay in the inner loop until it is completed, and then it will exit to the

outer loop. The outer loop will increment outer by one, and since outer is

still within its range, it will enter the outer loop body, which, once again,

will reach the inner loop. Since we left the inner loop once already, reaching

the inner loop this time is like reaching it for the first time. The statement

for inner in range(0, 3) sets inner to 0 once again, and the process

repeats itself.

We often use nested loops to write programs in Python. For one example, suppose we wish to write a program that repeatedly asks for students’ names and exam scores. The output should be students’ names followed by their exam average. Listing 3.43 shows how to do this using nested loops.

1student = input("Student name? ('quit' to end) ")

2while student != "quit":

3 sum = 0.0

4 count = 1

5 score = input("Score %d? ('quit' to end) " % count)

6 while score != "quit":

7 score = float(score)

8 sum += score

9 count += 1

10 score = input("Score %d? ('quit' to end) " % count)

11

12 # count is one more than it should be since we

13 # increment count before we quit.

14 count -= 1

15

16 if count > 0:

17 average = sum / count

18 print("%s's average is %.2f" % (student, average))

19 else:

20 print("No grades entered for %s." % student)

21

22 student = input("Student name? ('quit' to end) ")

One thing to note about this code, besides the nested while loops, is the

shorthand assignment statements. Instead of typing

count = count + 1

we can type

count += 1

This type of shorthand assignment construct works for most operators in Python.

Beyond that observation, we note that the outer while loop is responsible for

getting each student’s name. The inner while loop retrieves each score and

adds it to a sum. Once we exit the inner loop, we can calculate the average

using the sum. We must be careful to make sure that there are any scores at

all. If count were 0 and we divided by 0 without checking, our program

would crash.

The output of this code might look something like the following depending on what the user types.

Student name? ('quit' to end) David Chan

Score 1? ('quit' to end) 95.5

Score 2? ('quit' to end) 80.5

Score 3? ('quit' to end) 87.0

Score 4? ('quit' to end) quit

David Chan's average is 87.67

Student name? ('quit' to end) Sarah McDowell

Score 1? ('quit' to end) quit

No grades entered for Sarah McDowell.

Student name? ('quit' to end) quit

3.7. Exercises¶

Write a program that asks for a word, phrase, or sentence. The program should then print whether the input is a palindrome. (Do a Web search to see what a palindrome is.)

Write a program that repeatedly asks for a number until the user enters “quit.” The program should print the sum and average of all the numbers.

What is the output of the following program?

for i in range(2, 10, 2): print(i)

What is the output of the following program?

for i in range(5, 0, -1): print(i)

What is the output of the following program?

for i in range(1, 6, 2): for j in range(1, 3): print("%d %d" % (i, j))

Write an English-to-Pirate translator like the one found in Section 3.5, only have your program repeatedly ask for sentences until the user presses ENTER/RETURN without typing anything. You can still ignore capitalization and punctuation.

Do the previous problem again, only this time properly handle capitalization and punctuation.

Write a program that translates English sentences to Pig Latin.

To form the Pig Latin equivalent of a word, remove the first consonant sound of the word and append it to the end preceded by a dash and followed by “ay”. Thus, “cat” becomes “at-cay” and “ship” becomes “ip-shay.” The latter example demonstrates that consonant sounds can be blended consonants.

If an English word begins with a vowel, the word is simply restated with “-way” appended to it. In other words, “apple” becomes “apple-way.” Your solution should handle capitalization and punctuation.

Example of a working program:

Enter English (press 'ENTER' only to quit): Hey there, Delilah! The Pig Latin equivalent is: Ey-hay ere-thay, Elilah-day! Enter English (press 'ENTER' only to quit): Welcome to the Apple Store. The Pig Latin equivalent is: Elcome-way o-tay e-thay Apple-way Ore-stay. Enter English (press 'ENTER' only to quit): Thank you for using the Pig Latin translator!

Write a program that asks for a number and then prints that number of rows of 5 asterisks. For example, if the user enters 4, the program would print the following.

***** ***** ***** *****

Write a program that asks for two numbers x and y. The program should print a rectangle of asterisks consisting of x rows and y columns. For example, if the user enters 3 and 8, respectively, the program would print the following.

******** ******** ********

Write a program that asks for a number and then prints a triangle of asterisks where the base has that number of asterisks. For example, if the user enters 4, the program would print the following.

* ** *** ****

Write a program that asks for a number and then prints an inverted triangle of asterisks where first row contains that number of asterisks. For example, if the user enters 4, the program would print the following.

**** *** ** *

Python programs are capable of generating random numbers (well, “pseudo”-random numbers – more about that in the next chapter). One example of how to do this is as follows.

import random x = random.randint(1,10) print("Here is a random integer between 1 and 10: %d" % x)If you run this program over and over again you’ll see the number change. We can use random integers to simulate real-life occurrences, including games of chance and movement of animals.

Consider one program that demonstrates the use of random numbers. A drunkard stumbling around in a grid of streets picks one of four directions (north, south, east, or west) at each intersection, and then he moves to the next intersection.

Write a program that simulates the drunkard’s walk. Represent each intersection location as (x,y) integer pairs and have the drunkard start at (0,0). Have the drunkard walk 100 intersections and print the intersection location where he ends up. Run this program many times. Does the drunkard tend to stay close to (0,0) or does he end up moving far away?