2. Conditionals¶

2.1. The if statement and the Boolean type¶

Do you remember our sample program involving cats in Chapter 1? Let’s re-write it here in Listing 2.1.

1cats = int(input("How many barn cats do you own? "))

2cats = cats * 2

3print("In a six-months, you will have %d cats!" % cats)

Feral barn cats can multiply rapidly if not spayed or neutered, so this is not that ridiculous of an example. Suppose we want our program to make the observation “That’s a lot of cats!” if the barn owner ends up with more than 20 cats. Our first attempt at this, based on what we know so far, might look like this.

1cats = int(input("How many barn cats do you own? "))

2cats = cats * 2

3print("In a six-months, you will have %d cats!" % cats)

4print("That's a lot of cats!")

Python programs always execute in sequence. That is, first Python executes line 1, then line 2, line 3, and finally line 4. With that in mind, line 4 will always execute no matter what. This is absurd given what we are trying to accomplish, and even more absurd if the user types 0 for the number of cats initially.

What we need is a way to say “only print if the number of cats is 20 or more.”

Python allows us to do this by using something called an if statement. Let’s

modify our code as follows in Listing 2.3.

1cats = int(input("How many barn cats do you own? "))

2cats = cats * 2

3print("In a six-months, you will have %d cats!" % cats)

4if cats > 19:

5 print("That's a lot of cats!")

Notice how we’ve added a line just before our final print statement. Note also how our print statement in line 5 is now tabbed over one tab-stop. Now try out your program using several different inputs for cats. It works!

To understand more about why it works and how if statements work in general, let’s add one more line of code (for now).

1cats = int(input("How many barn cats do you own? "))

2cats = cats * 2

3print("In a six-months, you will have %d cats!" % cats)

4if cats > 19:

5 print("That's a lot of cats!")

6print("Thank you for using our program.")

Try out your program using several different inputs for cats again. Notice how no matter how many cats you enter, the program always prints “Thank you for using our program.” Now, let’s tab the last line over one tab-stop so that it lines up with the previous print statement.

1cats = int(input("How many barn cats do you own? "))

2cats = cats * 2

3print("In a six-months, you will have %d cats!" % cats)

4if cats > 19:

5 print("That's a lot of cats!")

6 print("Thank you for using our program.")

Try out your program again.

Notice how now the program only prints “Thank you for using our program.” if the

value of cats is greater than 19. This tells us something about how if

statements work. When the expression cats > 19 is true, any statements that

are indented beneath the if statement are executed, but they are only executed

if the expression cats > 19 is true. A sequence of statements separated

together by indentation (i.e., tabs) is called a block of statements.

Let’s try one more thing to understand how tabs/indentation work. What happens

if we de-indent line 5, i.e., the first line under the if?

1cats = int(input("How many barn cats do you own? "))

2cats = cats * 2

3print("In a six-months, you will have %d cats!" % cats)

4if cats > 19:

5print("That's a lot of cats!")

6 print("Thank you for using our program.")

Run your code. Kablooey! The error indicates that whenever Python sees an

if, there should be at least one indented statement or block of code beneath

it.

Earlier, we referred to cats > 19 as an expression. If it is an expression,

then it must produce a value and must have a type, right? Let’s go to our

Python Shell window and type the following: type(cats > 19). The result we

are given is something called a bool. The word “bool” stands for Boolean.

The word Boolean refers to the work of George Boole, an English mathematician

who formalized mathematical logic. Valid Boolean values are either True

or False.

Whenever the value of the Boolean expression given to an if statement is

True, the indented block of code beneath it will be executed. If it is

False, the block will be skipped.

Based on what we know about variables having types, we might conclude that we can create Boolean variables, too, and we’d be right! Consider the code in Listing 2.7.

1cats = int(input("How many barn cats do you own? "))

2cats = cats * 2

3print("In a six-months, you will have %d cats!" % cats)

4

5too_many = cats > 19

6if too_many:

7 print("That's a lot of cats!")

8

9print("Thank you for using our program.")

Now, suppose we want to say “You should get more cats” if the barn owner does

not yet have 20 cats. That is, we want to say this message if the Boolean

expression is False. We can adjust our code by changing this:

if cats > 19:

print("That's a lot of cats!")

to this:

if cats > 19:

print("That's a lot of cats!")

else:

print("You should get more cats.")

Any if block can have an else block to handle situations where the if

condition is False. Having an else block is always optional.

Boolean expressions can be formed using logical operators. We’ve already seen

greater-than (>). Table 2.1 shows the rest of the

logical operators in Python. Note that, for example, >= denotes

greater-than-or-equal-to, presumably because the symbol ( geq ) does not

exist on your computer keyboard. Also, note that comparing two values for

equality uses the == double-equals symbol. We already use the equals

(=) symbol for assignment statements so ==

is used to compare two values as part of a Boolean expression.

Operator |

Description |

|---|---|

|

equals |

|

not equals |

|

greater than |

|

greater than or equal to |

|

less than |

|

less than or equal to |

2.2. elif and Boolean Operators¶

Different states in the U.S.A. have different rules for when one is allowed to obtain a license to drive an automobile. One common practice is to allow individuals who are 16 or older to get a license. Suppose we wished to write a Python program that tells people if they are eligible to obtain a driver’s license in their state. We might prompt users for their respective ages, and then we could respond appropriately. Let’s use the code in Listing 2.8 as our starting point.

1age = int(input("What is your age? "))

2if age >= 16:

3 print("You are old enough to take your license exam.")

4else:

5 print("Perhaps you should ride a bike for now.")

The situation in some states is more involved than this. In fact, let us suppose that if users are 14 or older, they can obtain a learner’s permit where they are able to drive if accompanied by an adult. If they are 16 and they also have had a driver’s education class, then they can take the license exam. Got it? Let’s ignore driver’s education for right now to simplify things, and let’s try to re-write our program using what we know so far:

age = int(input("What is your age? "))

if age >= 14:

print("You may obtain a learner's permit.")

else:

if age >= 16:

print("You are old enough to take your license exam.")

else:

print("Perhaps you should ride a bike for now.")

That’s a lot of indentation! Fortunately, the indentation makes the logic of

our code a bit easier to follow, which is a nice feature of Python code. When

we reach the first else, our code beneath the else starts at a new

indentation level.

Try running this code using a variety of inputs. Do you notice a problem?

It appears that no matter what age we enter, we can never get it to tell us

we’re old enough to take the license exam. Our Boolean conditions are not in

the correct order. Even if we type that we are 17 years old, for example, the

first condition is True, so it prints “You may obtain a learner’s permit.”

Let’s fix the order of our code to place the most restrictive Boolean expression

first:

age = int(input("What is your age? "))

if age >= 16:

print("You are old enough to take your license exam. ")

else:

if age >= 14:

print("You may obtain a learner's permit.")

else:

print("Perhaps you should ride a bike for now.")

This is much better.

You might imagine that if you have a lot of different conditions you wish to

handle in your program, your code many eventually look like a very long series

of stair steps. This would make our code a bit difficult to read and maintain,

so Python provides us with a statement for making a series of else-if

conditions. This statement is called elif, for short. We can re-write the

code above as follows:

age = int(input("What is your age? "))

if age >= 16:

print("You are old enough to take your license exam. ")

elif age >= 14:

print("You may obtain a learner's permit.")

else:

print("Perhaps you should ride a bike for now.")

print("Done.")

Note that we’ve also added a statement that prints “Done” for illustrative purposes.

Having elif’s work the same way as having an else block followed by an if

block. If the first condition is True, we print that we are old enough to

take the exam. Then, none of the other conditions are checked. Instead, Python

drops down to the “Done” print statement. If the first condition is False,

then, and only then, is the next condition checked. If that condition is

True, we print that they can obtain a learner’s permit and we drop down to the

“Done” print statement. If that condition was False, our code descends to

the else block.

else blocks are always optional. elif blocks are also optional. You can

have any number of elif blocks, but if/elif/else blocks must

always come in this sequence:

first an

ifstatementthen any

elif’sfinally an

else

Now let’s consider driver’s education in our example. Individuals must be 16

years old and have had a driver’s education class to take the license exam. So,

we’ll need to ask them if they’ve taken the exam by using another input

statement.

1age = int(input("What is your age? "))

2drivers_ed = input("Have you passed driver's education? (y/n) ")

3if age >= 16:

4 print("You are old enough to take your license exam. ")

5elif age >= 14:

6 print("You may obtain a learner's permit.")

7else:

8 print("Perhaps you should ride a bike for now.")

9print("Done.")

Notice how we are prompting users to enter either "y" or "n" for their

answer to the driver’s education question. Also notice that we do not need to

cast the value returned from the input function to another type like we did in

the previous input statement (the one that asks for the age). The variable

drivers_ed can remain a string, because "y" or "n" are string values.

Now, let’s adjust our logic. We’ll only show the part of the code that deals with taking the license exam for now. This code:

if age >= 16:

print("You are old enough to take your license exam. ")

can become this code:

if age >= 16:

if drivers_ed == "y":

print("You are old enough to take your license exam. ")

This new code says that in order to print "You are old enough to take your

license exam" first age >= 16 must be True, and then drivers_ed == "y"

must be True, too.

There is another way to do this that you might like better. We can use something called a Boolean operator. Instead of this:

if age >= 16:

if drivers_ed == "y":

print("You are old enough to take your license exam. ")

we can say this:

if age >= 16 and drivers_ed == "y":

print("You are old enough to take your license exam. ")

The and keyword is the Boolean operator. We can now modify Listing 2.9 as follows in Listing 2.10.

1age = int(input("What is your age? "))

2drivers_ed = input("Have you passed driver's education? (y/n) ")

3if age >= 16 and drivers_ed == "y":

4 print("You are old enough to take your license exam. ")

5elif age >= 14:

6 print("You may obtain a learner's permit.")

7else:

8 print("Perhaps you should ride a bike for now.")

9print("Done.")

When we join two separate Boolean expressions together with the keyword and,

the resulting expression is True only if both of the expressions are each

True. If either age >= 16 is False or drivers_ed == "y" is False,

then the whole Boolean expression age >= 16 and drivers_ed == "y" is

False.

There are three Boolean operators in Python, which are given in Table 2.2.

Operator |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Suppose If If If If In other words, the expression |

|

Suppose If If If If In other words, the expression |

|

Suppose If If |

Let us look at another example where these Boolean operators become useful. Suppose we want to write a program that tells people if they have an increased risk for heart disease. There are a number of known risk factors, but for now we’ll only consider three. Without Boolean operators, we might write the program in Listing 2.11.

1bp = input("Do you have high blood pressure (y/n)? ")

2smoke = input("Do you smoke (y/n)? ")

3hist = input("Do you have a family history of heart disease (y/n)? ")

4

5if bp == "y":

6 print("You have an increased risk of heart disease.")

7elif smoke == "y":

8 print("You have an increased risk of heart disease.")

9elif hist == "y":

10 print("You have an increased risk of heart disease.")

11else:

12 print("You do not have an increased risk for heart disease.")

Note that each of the statements that follow the if/elif conditions all

print the same message. Instead, we can use the Boolean operator or to

simplify the code resulting in Listing 2.12.

1bp = input("Do you have high blood pressure (y/n)? ")

2smoke = input("Do you smoke (y/n)? ")

3hist = input("Do you have a family history of heart disease (y/n)? ")

4

5if bp == "y" or smoke == "y" or hist == "y":

6 print("You have an increased risk of heart disease.")

7else:

8 print("You do not have an increased risk for heart disease.")

Lastly, we can use the not operator to improve the readability of code.

Recall how, in our driver’s license example

(Listing 2.10), we asked if the user had taken a driver’s

education course. With this scenario in mind, consider the following

(Listing 2.13).

1age = int(input("What is your age? "))

2drivers_ed = input("Have you taken driver's ed (y/n)? ") == "y"

3if 14 <= age and age <= 16 and not drivers_ed:

4 print("You should consider taking a driver's ed course.")

This example includes a few interesting code constructions. Line 2 of

Listing 2.13 is different from what you’ve seen

before. Previously in Listing 2.10, we let

drivers_ed be a string

variable whose value should be "y" or "n". In this code, drivers_ed is a

Boolean variable. Why?

Notice that the input part of the statement is followed by a logical operator,

the double-equals (==). Thus, we are comparing what the user types to the

string "y". If the user typed "y", then the RHS of the assignment statement

is True, so drivers_ed gets the value True. If the user types anything

else, drivers_ed becomes False.

Next, we have code that checks to see if the user age’s is still typically in

the range that students take a driver’s education class. If so, and they’ve not

had driver’s education, they are advised to do so via a print statement. The

only way the print statement will happen is if the age is between 14 and

16, and they’ve not had driver’s education.

Keep in mind that the programming practice in line 2 of

Listing 2.13 might not be a good idea. Your author

has only written code this way to show you that it can be done. The latter

part of the expression (== "y") might be hard to notice, and because it is

hard to notice, it may make the code more difficult to read and therefore

maintain. In the future, we may want to check what the user typed in to make

sure it’s what we expect (i.e., a "y" or a "n"). Checking inputs is

something we’ll discuss in Chapter 4: Loops.

2.3. Nuances of Boolean operators¶

Students will sometimes write code like this:

age = int(input("What is your age? "))

if age == 14 or 15:

print("You can get a learner's permit.")

Run this code and type 18. Uh oh. Why does it print “You can get a learner’s

permit”?

Remember than anything on the LHS and RHS of a Boolean operator must be itself a

Boolean expression. In other words, the LHS and RHS must both be True or

False. In the above example, there is an expression on either side of the

double-equals. One is:

age == 14

and the other is:

15

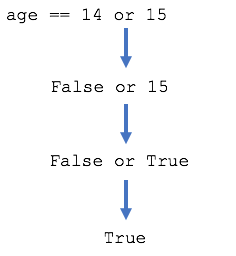

The expression age == 14 is False. The expression 15 is True.

Anything non-zero in Python is treated as True. Therefore, the Boolean

expression is “transformed” as in Figure 2.1.

Fig. 2.1 Evaluating a Boolean or¶

Instead of:

age == 14 or 15

a programmer should write:

age == 14 or age == 15

Bottom line: be very careful when using and/or.

2.4. Exercises¶

Suppose

xis an integer variable. What is the difference between the expressionx = 2and the expressionx == 2?Given the following variable definitions,

x = 3 y = 6

what is the type and value of each of the following expressions?

x != 0 y >= 3 x == y not (x == 0) x > 1 and y < 5 2 < x and x < 5 7 < y or y < 10

Identify the error in the following code.

num = float(input("Enter a real number: ")) if num < 0.0: print("%.2 is negative." % num) else: print("The number is 0.0.") elif num > 0.0: print("%.2 is positive." % num)

Identify the error in the following code.

num = float(input("Enter a real number: ")) if num = 0.0: print("The number is 0.0.") elif num < 0.0: print("%.2 is negative." % num) else: print("%.2 is positive." % num)

What is the output of the following code?

major = "Music" if major == "Computer Science" or "Math": print("Calculus is required for your major.") elif major == "Music": print("Music Theory is required for your major.")

Consider the following code.

if a > 2: if b < 3: print("Statement 1") else: print("Statement 2") else: if b > 3: print("Statement 3") else: print("Statement 4")

What is the output of the program if

aandbwere given the following values prior to the start of the code?a = 3 b = 4 a = -2 b = 2

What is the output of the following code.

r = 10 if 5 < r and r < 15: print("1") if 5 < r or r < 15: print("2") r = 100 if 5 < r and r < 15: print("3") if 5 < r or r < 15: print("4")

Write code that rounds a float number up or down without using the

roundfunction introduced in Chapter 1. That is, write code that asks for a number, and then it takes that number and rounds it up or down appropriately without relying on theroundfunction. For example, if the user types3.6, the program should output a4since the fractional part.6is greater than.5. The user were to type3.2, the program should output a3since the fractional part.2is less than.5.It may help to know that if you use the

intfunction to cast a float to an integer, the fractional part disappears. This is called truncation. For example, in the following codef = 3.6 i = int(f)

the value of

iends up being3.